VTEnc, a new inverted list compressor

In this post, I’m going to introduce what I believe is a novel integer compression method that I’ve come up with: VTEnc.

VTEnc is an inverted list compressor, a type of integer compressor that encodes a whole integer list, instead of representing each single integer separately. An inverted list is basically a non-decremental sequence of non-negative integers.

VTEnc is an acronym for Vertically-Clustered Bits Tree Encoding. This long name describes quite accurately how the algorithm works, though it’s not obvious what that bunch of words mean together. In the next sections, I’ll break that phrase down into smaller parts so that I can explain them separately and step by step.

Vertically-Clustered Bits

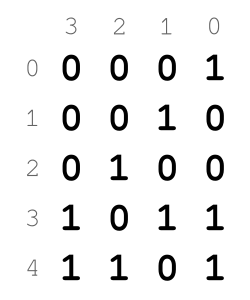

The first step of the algorithm is to group bits vertically. For that, we first need to represent the input list in binary and think of it as a table. Rows correspond to the values of the list, numbered 0 through \(N-1\), \(N\) being the size of the list. Columns are the bit positions, numbered 0 through \(W-1\), where \(W\) is the size in bits of each integer in the list. In this table, rows follow a top-to-bottom order and columns conform to a right-to-left arrangement.

As an example, the figure above shows the binary table of the sequence of 4-bit integers [1, 2, 4, 11, 13]. In light grey, you can see the horizontal and vertical indexes. I’ll be referring to this very example to illustrate the different stages of the algorithm throughout this post.

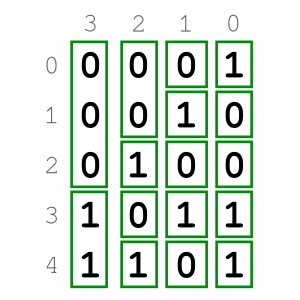

VTEnc creates clusters by bringing together consecutive bits that have the same value and belong to the same column.

However, not all the clusters are allowed. VTEnc adds a restriction that needs to be met: each cluster is vertically constrained by the adjacent cluster on its left. That means that a) none of the clusters extends out of the vertical bounds marked by its neighbouring cluster on its left; and b) a cluster can only have one contiguous cluster on its left. Of course, this restriction doesn’t apply to clusters in column \(W-1\) as that’s the leftmost column. Notice that, for instance, the two possible clusters of two bits each in column 0 (rows 1-2 and 3-4) in the example above are not permitted.

An interesting property appears when including the constraint I just explained: any cluster in any column greater than 0 has only one or two adjacent clusters on its right. It’s beyond the scope of this post to prove it, but the relevant thing here is that this property is only true for sorted lists of non-negative integers, like VTEnc’s input. This characteristic is essential for the next step of the algorithm.

Tree

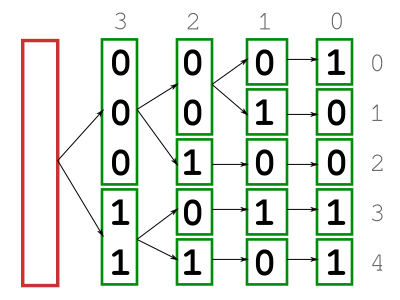

The purpose of arranging clusters in this particular way is to ease the creation of a tree out of them. If you think of a cluster as a node within a tree and set it up to be the parent node of its contiguous clusters on its right, then we have almost built a binary tree. We still need to set a root node; I’ll explain how to do so shortly.

Here is the binary tree from the clusters in the previous example:

Nonetheless, the tree we want to build here is not exactly as the one from the figure above. We don’t care about the specific bits that make up a cluster. Instead, we just use the lengths of the clusters to be the nodes of the tree. For the root node, we use the length of the whole input list.

So far, we have defined the nodes and their relationships. The final binary tree is completed with the properties listed below:

- Left-child nodes correspond to clusters that held 0s, whereas right-child nodes correspond to clusters with 1s.

- The height of the tree is \(W+1\).

- Any non-leaf, non-zero-value node has exactly two children nodes.

- Each node in (3) has a value equal to the sum of its children nodes.

In order to accomplish (3) and (4), the tree must be extended by adding a 0-value node to nodes with only one child.

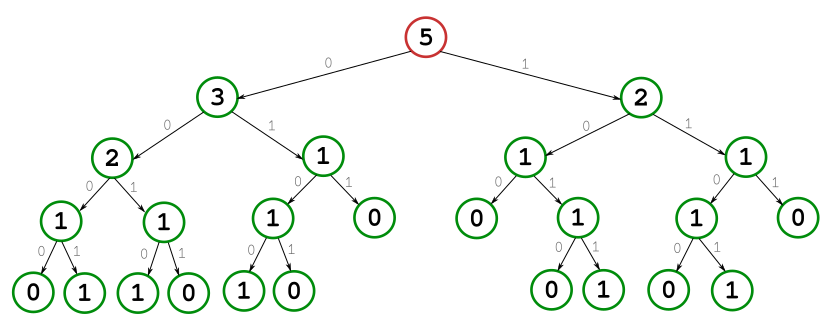

Continuing with the same example, this is the final tree:

Encoding

Once the binary tree has been built, it’s time to encode it. The encoding phase has two parts: tree serialisation and tree encoding. They don’t take place separately, but I’ll describe them so for the sake of clarity.

VTEnc follows a pre-order traversal system to serialise the tree. By using this method, the tree is transformed into a sequence of integers in the order in which its nodes are visited. Here we don’t need to serialise every single node, we can actually skip (roughly) half of them and still get a sequence that represents the original tree. The trick lies in taking advantage of the properties listed in the previous section. We know that the sum of the two children nodes is equal to their parent’s value. Consequently, knowing the value of a parent node and one of its children is enough information in order to calculate the value of the other child. VTEnc leverages this property and only serialises the root node and all the left-child nodes.

A full serialisation for the tree of the previous example would produce this sequence:

5, 3, 2, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 2, 1, 0, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 0, 1, 0

In contrast with the actual sequence you get when using the optimisation I just explained:

5, 3, 2, 1, 0, 1, 1, 1, 1, 0, 0, 1, 0

VTEnc uses a simple encoding scheme. Every node of the tree is encoded with the minimum number of bits required to represent its parent node. In other words, the length in bits \(b\) with which a node \(n\) is encoded is defined by the following expression:

\[b = \begin{cases} 1 & \quad \text{if } parentValue(n) = 0\\ \lceil\log_2(parentValue(n) + 1)\rceil & \quad \text{if } parentValue(n) > 0 \end{cases}\]where \(parentValue(n)\) is the value of the parent node of \(n\). The root node is encoded with \(W\) bits. This technique is covered in more depth here and here.

0101, 011, 10, 01, 0, 1, 1, 1, 01, 0, 0, 1, 0

Above you can see the outcome of encoding the binary tree of the example we’ve been following in this article. The resulting stream has a length of 21 bits in total, 1 bit more than the original input list.

So, where is the compression gain?

We’ve seen that applying VTEnc to the example above generates an output larger than the input. That’s not a desirable result, but using VTEnc doesn’t guarantee to always get a compression ratio \(\geq\) 1.0. For tiny lists like the one from the example, it is quite likely you’ll get a slightly bigger output. Most compression methods face the same issue when dealing with such small inputs.

Besides small inputs, you should always get a compressed output when using VTEnc.

How VTEnc compresses

The key step with which VTEnc achieves compression is creating a tree node from a cluster of bits. Concretely, the sequence of bits that make up a cluster is represented with a single number: its length. This process is somehow similar to what Run-length encoding (or RLE) does since it replaces a sequence of identical symbols with something else. However, unlike RLE that substitutes the sequence with two symbols (original symbol and count), we only need the sequence’s length as the repeated value (0 or 1) is known.

Following, there is a table with some ideal compression ratios for some cluster lengths (or node values). Although a given cluster length may be encoded with more bits than the optimal value shown in the second column, you can see a trend here: the larger a cluster is, the greater its compression ratio. Hence, a considerable part of the compression is accomplished when encoding clusters in columns close to the table’s left bound or, in other words, when encoding nodes close to the root.

length enc. bits comp. ratio

1 1 1.0

2 2 1.0

6 3 2.0

10 4 2.5

20 5 4.0

30 5 6.0

100 7 14.3

1000 10 100.0

Another step that contributes to the compression gain is the tree serialisation. As explained earlier, we only serialise half of the tree’s nodes. You might then think that a compressed output should be at least half of the input’s size. Unfortunately that’s not true. You’ll recall that the tree is also extended by adding some leaf nodes, so in the end, some of those extra nodes added compensate some of the nodes skipped when serialising. But not all of them. The non-leaf nodes omitted during the serialisation also play an important role in the compression gain.

Finally, the encoding method employed by VTEnc fits quite well for the kind of small numbers which are encoded. This process doesn’t implicitly help to get a more squeezed output, but it doesn’t add much overhead either.

Wrapping up

The sole aim of this article is to introduce this new compression algorithm. That includes explaining the details about it and also trying to uncover how it compresses. I’ve deliberately left out things like measuring its performance in terms of speed and compression ratio, or comparing it to other integer compression methods. Those things are linked to the implementation specifics and they’ll be part of the next posts to come.